♘امیرحسین♞

♘ مدیریت انجمن اسب ایران ♞

Laminitis is a disease of the sensitive laminae of the foot in a horse. The front hooves are most commonly affected, although the hind feet are sometimes affected. Its name means inflammation of the laminae, although inflammation is no longer considered as the key mechanism of the disease process.

Foundering and sinking

Rotation and sinking are two possible consequences of a single severe laminitic episode or of repeated episodes. The latter is less common and much more severe.

Sinking results when there is a cataclysmic failure of the interdigitation between the sensitive and insensitive laminae around the entire perimeter of the hoof. Apparently this event allows the entire bony column, often described by its most distal bone, the third phalanx (a.k.a. PIII, P3, coffin bone, pedal bone, distal phalanx) to sink within the bottom of the hoof capsule. In the UK, this sequel is also commonly called "founder", from the nautical term "to sink". In the U.S.A., founder has come to mean any chronic changes in the structure of the foot. In some texts, the term "founder" is now used synonymously with laminitis.

Rotation occurs when the damage to the laminae is less severe and it will show up mainly in the toe area of the foot. One possible reason for this is the pull of the tendon attached to the coffin bone, the deep flexor tendon, literally pulling the dorsal face of the coffin bone away from the inside of the hoofwall. It is also theorized that the body weight of the animal contributes to rotation of the coffin bone. Rotation results in an obvious misalignment between PII (the short pastern bone) and PIII (the coffin bone). In some cases, the rotation may also result in the tip of PIII penetrating the sole and becoming exposed externally.

Depending upon the severity at the onset of the pathology, there may be no movement of the pedal bone, rotation only, sinking only or a combination of both rotation and sinking, to varying extents. It is generally agreed that a severe "sinker" warrants the gravest prognosis and may, depending upon many factors, including the quality of after care, age of the horse, diet and nutrition, skill, knowledge and ability of the attending veterinarian and farrier(s), lead to euthanasia of the patient.

Not all horses that experience laminitis will founder but all horses that founder will first experience laminitis.

In laminitis cases, a clear distinction must be made between the acute situation, starting at the onset of a laminitis attack and a chronic situation. A chronic situation can be either stable or unstable. The difference between acute, chronic, stable and unstable is of vital importance, when choosing a treatment protocol.

Laminitis can be mechanical or systemic, unilateral (on one foot) or bilateral (on two feet) or may also occur in all four feet.

Systemic laminitis follows from some metabolic disturbance within the horse, from a multitude of possible causes, and results in the partial dysfunction of the epidermal and dermal laminae, which attach the distal phalanx to the hoof wall. With this dysfunction, the deep digital flexor tendon (which attaches to the semi-lunar crest of the distal phalanx and serves to flex the foot) is able to pull the bone away from the wall, instead of flexing the foot. When the coffin bone is pulled away from the hoofwall, the remaining laminae will tear. This may lead to abscesses, within the hoof capsule, that can be severe and very painful. Also, a laminar wedge may form, between the front of the hoof wall and the pedal bone. This laminar wedge may, in some cases, prevent the proper re-attachment (interdigitation) of the laminae. Under certain conditions and only after consultation with an experienced veterinarian and farrier team, a dorsal hoof wall resection, to remove this laminar wedge, may be undertaken.

Systemic laminitis is usually bilateral and is most common in the front feet, although it sometimes affects the hind feet.

Mechanical laminitis or "mechanical founder" does not start with laminitis or rotation of the distal phalanx. Instead, the wall is pulled away from the bone or lost, as a result of external influences. Mechanical founder can occur when a horse habitually paws, is ridden or driven on hard surfaces or loses laminar function, due to injury or pathologies affecting the wall.

Mechanical founder can be either unilateral or bilateral and can affect both front and hind feet.

It is important to note that, once the distal phalanx rotates, it is essential to de-rotate and re-establish proper spatial orientation of p3 within the hoof capsule, to ensure the best long-term prospects for the horse. With correct trimming and, as necessary, the application of orthotics, one can effect this re-orientation. This attempt at re-orientation may be less than one hundred per cent effective, however.

Successful treatment for any type of founder must necessarily involve stabilization of the bony column by some means. Stabilization can take many forms but most include trimming the hoof to facilitate "break over" and trimming the heels to ensure frog pressure. While some horses stabilize if left barefooted, some veterinarians believe that the most successful methods of treating founder involve positive stabilisation of the distal phalanx, by mechanical means, e.g., shoes, pads, polymeric support, etc.

Steps taken to stabilize the bony column gain maximum effect when combined with steps that will reduce the pulling force of the flexor tendon attached to the coffin bone, the deep flexor tendon.

Causes of laminitis

Many cases of laminitis are caused by more than one factor and are rather due to a combination of causes.

Carbohydrate overload

One of the more common causes. Current theory states that if a horse is given grain in excess or eats grass that is under stress and has accumulated excess non-structural carbohydrates (NSC, i.e. sugars, starch or fructan), it may be unable to digest all of the carbohydrate in the foregut. The excess then moves on to the hindgut and ferments in the cecum. The presence of this fermenting carbohydrate in the cecum causes proliferation of lactic acid bacteria and an increase in acidity. This process kills beneficial bacteria, which ferment fiber. The endotoxins and exotoxins may then be absorbed into the bloodstream, due to increased gut permeability, caused by irritation of the gut lining by increased acidity. The endotoxaemia results in impaired circulation, particularly in the feet. This results in laminitis.

Insulin resistance

Laminitis can also be caused by insulin resistance in the horse (See also Equine Metabolic Syndrome, below. Insulin resistant horses tend to become obese very easily and, even when starved down, may have abnormal fat deposits in the neck, shoulders, loin, above the eyes and around the tail head, even when the rest of the body appears to be in normal condition. The mechanism by which laminitis associated with insulin resistance occurs is not understood but may be triggered by sugar and starch in the diet of susceptible individuals. Ponies and breeds that evolved in relatively harsh environments, with only sparse grass, tend to be more insulin resistant, possibly as a survival mechanism. Insulin resistant animals may become laminitic from only very small amounts of grain or "high sugar" grass. Slow adaptation to pasture is not effective, as it is with laminitis caused by microbial population upsets. Insulin resistant horses with laminitis should be removed from all green grass and be fed only hay that is tested for Non Structural Carbohydrates (sugar, starch and fructan) and found to be below 11% NSC on a dry matter basis. Soaking hay underwater may remove excess carbohydrates and should be part of a first-aid treatment for any horse with laminitis associated with obesity or abnormal fat deposits. This can have the effect of depleting the hay of soluble minerals and vitamins, however, so care with dietary balance is important.

Nitrogen compound overload

Herbivores are equipped to deal with a normal level of potentially-toxic non-protein nitrogen (NPN) compounds in their forage. If, for any reason, there is rapid upward fluctuation in levels of these compounds, for instance in lush spring growth on artificially fertilized lowland pasture, the natural metabolic processes can become overloaded, resulting in liver disturbance and toxic imbalance. For this reason, many avoid using artificial nitrogen fertilizer on horse pasture. If clover is allowed to dominate the pasture, this may also allow excess nitrogen to accumulate in forage, under stressful conditions such as frost or drought. Many weeds eaten by horses are nitrate accumulators. Direct ingestion of nitrate fertilizer material can also trigger laminitis, via a similar mechanism.

Hard ground

Whenever possible, avoid working horses on hard ground. This includes concrete or gravel roads. An indoor or outdoor arena should be periodically dragged with a rake, to loosen the soil and to prevent it from hardening. Hard surfaces increase the concussion upon the horse's feet. The greater and more prolonged the concussion, the more likely it is that the horse will contract laminitis.

Lush pastures

When releasing horses back into a pasture, after being kept inside (typically during the transition from winter stabling to spring outdoor keeping), it is important to re-introduce them gradually. Feed horses before turning them out and limit the amount of time outside (45 minutes to an hour at first, gradually increasing the amount of time) and decrease the amount fed to them beforehand, as the season progresses. If a horse consumes too much lush pasture, after a diet of dry hay, the excess carbohydrate of grass can be a shock to its digestive system. If the horse is fed beforehand, it will not eat as much fresh grass when turned out and will be less likely to founder. It is also true that ponies are much more susceptible to this form of laminitis than are larger horses.

Frosted grass

Some cases of laminitis have occurred after ingestion of frosted grass. The exact mechanism for this has not been explained but sudden imbalance of the normal bowel flora can be surmised, leading to endotoxin production.

Freezing or overheating of the feet

Cases of laminitis have been observed following an equine standing in extreme conditions of cold, especially if there is a depth of snow. Laminitis has also followed prolonged heating such as may be experienced from prolonged contact with extremely hot soil or from incorrectly-applied hot-shoeing. In either case, it is possible to understand how the circulation of the feet may become adversely affected.

Cold exposure however has been shown to have a protective effect when horses are experimentally exposed to CHO overload. Feet placed in ice slurries were less likely to experience laminitis than "un-iced" feet.

Untreated infections

Infections, particularly where caused by bacteria, can cause release of endotoxins into the blood stream, which may trigger laminitis. A retained placenta in a mare (see below) is a notorious cause of laminitis and founder.

Colic

Laminitis can sometimes develop after a serious case of colic, due to the release of endotoxins into the blood stream.

Lameness

Lameness causes a horse to favor the injured leg, resulting in uneven weight distribution. This results in more stress on the healthy legs and can result in laminitis.

This may be the cause of the laminitis which caused owners to determine to put down 2006 Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro on January 29, 2007.

Cushing's disease

Cushing's disease is common in older horses and ponies and causes an increased predisposition to laminitis.

Peripheral Cushing's disease

Peripheral Cushing's disease (or more properly, Equine Metabolic Syndrome) is an area of much new research and is increasingly believed to have a major role in laminitis. It involves many factors such as cortisol metabolism and insulin resistance. It has some similarities to type II diabetes in humans (see also insulin resistance, described above). In this syndrome, peripheral adipocytes (fat cells) synthesise adipokines which are analogous to cortisol, resulting in Cushings-like symptoms.

Retained placenta

It is common practice, in horse-breeding establishments, to check by careful inspection that the entire placenta has been passed, after the birth of a foal. It is known that mares that retain the afterbirth can founder, whether through toxicity or bacterial fever or both.

Drug reactions

Anecdotally there have been reports of laminitis following the administration of drugs, especially in the case of corticosteroids. The reaction however may be an expression of idiosyncrasy in a particular patient as many horses receive high dose glucocorticoid into their joints without showing any evidence of clinical laminitis.

No evidence exists to show the mechanism by which glucocorticoids may trigger laminitis in the horse nor is there any research definitely proving a causal link between the two.

Exposure to agrichemicals

Even horses not considered to be susceptible to laminitis can become laminitic when exposed to certain agrichemicals. The most commonly-experienced examples are herbicide and synthesized nitrate fertilizer.

Symptoms of laminitis

* Increased temperature of the wall, sole and/or coronary band of the foot.

* A pounding pulse in the digital palmar artery. (The pulse is very faint or undetectable in a cold horse, readily evident after hard exercise.)

* Anxiety

* Visible trembling

* Increased vital signs and body temperature

* Sweating

* Flared Nostrils

* Walking very tenderly, as if walking on egg shells

* Repeated "easing" of affected feet

* The horse standing in a "founder stance" (the horse will attempt to decrease the load on the affected feet). If it has laminitis in the front hooves, it will bring its hindlegs underneath its body and put its forelegs out in front called "pointing"

* Tendency to lie down, whenever possible or, if extreme, to remain lying down.

The sooner the diagnosis is made the faster the treatment and the recovery process can begin. Diagnosing Laminitis is the main problem since the general problem often starts somewhere else in the horses body.

Complications of laminitis

Separation of the hoof wall

The destruction of the sensitive laminae results in the hoof wall becoming separated from the rest of the hoof. Pus may leak out at the white line or at the coronary band.

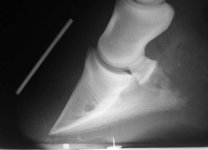

Rotation of the third phalanx

The third phalanx, also known as the coffin bone, rotates downward. Normally, the front of the third phalanx should be parallel to the hoof wall and its lower surface should be roughly parallel to the ground surface but, in laminitis, a combination of forces (e.g., the tension of the deep digital flexor tendon and the weight of the horse) allows the coffin bone to rotate. The degree of rotation may be determined by severity of the initial attack or by how soon laminitis is detected and how soon actions are taken to treat the horse.

Penetration of the third phalanx through the sole

If rotation of the third phalanx continues, its tip can eventually penetrate the sole of the foot. Penetration of the sole is not fatal; many horses have been returned to service by aggressive treatment by a veterinarian and farrier, but the treatment is time-consuming, difficult and expensive.

Treatment

There is no cure for a laminitic episode and many go undetected. However, a horse can live with laminitis for many years, and although a single episode of laminitis predisposes to further epidodes, with good management and prompt treatment, it is by no means the catastrophe sometimes supposed: most horses suffering an acute episode without pedal bone displacement make a complete functional recovery. Rest and corrective shoeing, can help improve a horse's condition. Common treatments involve pedal bone (PIII) support (either with commercially manufactured pads, or styrofoam blacks bandaged onto the feet), analgesics (usually phenylbutazone - "bute" - or suxibuzone - a related drug with fewer gastric side effects), and a vasodilator to improve laminar blood flow. Systemic acepromazine is commonly used for this purpose, as a powerful peripheral vasodilator with the fringe benefit of mild sedation which reduces the horse/pony's movements and thus reduces concussion on the hooves. Nitroglycerine may also be applied topically to increase blood flow. With modern treatment, most laminitics will be able to bear a rider or completely recover, if the laminitis was not severe or complicated (e.g. by Equine Metabolic Syndrome or Cushing's disease). Even in these cases, a clinical cure can normally be achieved. Endotoxic laminitis (e.g. after foaling) tends to be more difficult to treat. Successful treatment requires a competent farrier and veterinarian and success is not guaranteed. Alternative therapies such as herbal and homeopathic medicine may aid recovery but require expert veterinary input.

Complications from laminitis led to the euthanization of Barbaro, 2006 Kentucky Derby winner, in 2007.

The barefoot movement

Studies on hoof health by Dr. Hiltrud Strasser(Germany) and Jaime Jackson(U.S.) suggest an alternative, optimistic view on laminitis, which is supported by proponents of the barefoot horse movement. This is a holistic approach to the disease, mainly based on pulling shoes, proper hoof care and trimming, proper diet and movement. However, definitive studies as to the benefits in laminitic equines are still lacking. Cryotherapy may be one way to effectively treat laminitis in the developmental stages.

Foundering and sinking

Rotation and sinking are two possible consequences of a single severe laminitic episode or of repeated episodes. The latter is less common and much more severe.

Sinking results when there is a cataclysmic failure of the interdigitation between the sensitive and insensitive laminae around the entire perimeter of the hoof. Apparently this event allows the entire bony column, often described by its most distal bone, the third phalanx (a.k.a. PIII, P3, coffin bone, pedal bone, distal phalanx) to sink within the bottom of the hoof capsule. In the UK, this sequel is also commonly called "founder", from the nautical term "to sink". In the U.S.A., founder has come to mean any chronic changes in the structure of the foot. In some texts, the term "founder" is now used synonymously with laminitis.

Rotation occurs when the damage to the laminae is less severe and it will show up mainly in the toe area of the foot. One possible reason for this is the pull of the tendon attached to the coffin bone, the deep flexor tendon, literally pulling the dorsal face of the coffin bone away from the inside of the hoofwall. It is also theorized that the body weight of the animal contributes to rotation of the coffin bone. Rotation results in an obvious misalignment between PII (the short pastern bone) and PIII (the coffin bone). In some cases, the rotation may also result in the tip of PIII penetrating the sole and becoming exposed externally.

Depending upon the severity at the onset of the pathology, there may be no movement of the pedal bone, rotation only, sinking only or a combination of both rotation and sinking, to varying extents. It is generally agreed that a severe "sinker" warrants the gravest prognosis and may, depending upon many factors, including the quality of after care, age of the horse, diet and nutrition, skill, knowledge and ability of the attending veterinarian and farrier(s), lead to euthanasia of the patient.

Not all horses that experience laminitis will founder but all horses that founder will first experience laminitis.

In laminitis cases, a clear distinction must be made between the acute situation, starting at the onset of a laminitis attack and a chronic situation. A chronic situation can be either stable or unstable. The difference between acute, chronic, stable and unstable is of vital importance, when choosing a treatment protocol.

Laminitis can be mechanical or systemic, unilateral (on one foot) or bilateral (on two feet) or may also occur in all four feet.

Systemic laminitis follows from some metabolic disturbance within the horse, from a multitude of possible causes, and results in the partial dysfunction of the epidermal and dermal laminae, which attach the distal phalanx to the hoof wall. With this dysfunction, the deep digital flexor tendon (which attaches to the semi-lunar crest of the distal phalanx and serves to flex the foot) is able to pull the bone away from the wall, instead of flexing the foot. When the coffin bone is pulled away from the hoofwall, the remaining laminae will tear. This may lead to abscesses, within the hoof capsule, that can be severe and very painful. Also, a laminar wedge may form, between the front of the hoof wall and the pedal bone. This laminar wedge may, in some cases, prevent the proper re-attachment (interdigitation) of the laminae. Under certain conditions and only after consultation with an experienced veterinarian and farrier team, a dorsal hoof wall resection, to remove this laminar wedge, may be undertaken.

Systemic laminitis is usually bilateral and is most common in the front feet, although it sometimes affects the hind feet.

Mechanical laminitis or "mechanical founder" does not start with laminitis or rotation of the distal phalanx. Instead, the wall is pulled away from the bone or lost, as a result of external influences. Mechanical founder can occur when a horse habitually paws, is ridden or driven on hard surfaces or loses laminar function, due to injury or pathologies affecting the wall.

Mechanical founder can be either unilateral or bilateral and can affect both front and hind feet.

It is important to note that, once the distal phalanx rotates, it is essential to de-rotate and re-establish proper spatial orientation of p3 within the hoof capsule, to ensure the best long-term prospects for the horse. With correct trimming and, as necessary, the application of orthotics, one can effect this re-orientation. This attempt at re-orientation may be less than one hundred per cent effective, however.

Successful treatment for any type of founder must necessarily involve stabilization of the bony column by some means. Stabilization can take many forms but most include trimming the hoof to facilitate "break over" and trimming the heels to ensure frog pressure. While some horses stabilize if left barefooted, some veterinarians believe that the most successful methods of treating founder involve positive stabilisation of the distal phalanx, by mechanical means, e.g., shoes, pads, polymeric support, etc.

Steps taken to stabilize the bony column gain maximum effect when combined with steps that will reduce the pulling force of the flexor tendon attached to the coffin bone, the deep flexor tendon.

Causes of laminitis

Many cases of laminitis are caused by more than one factor and are rather due to a combination of causes.

Carbohydrate overload

One of the more common causes. Current theory states that if a horse is given grain in excess or eats grass that is under stress and has accumulated excess non-structural carbohydrates (NSC, i.e. sugars, starch or fructan), it may be unable to digest all of the carbohydrate in the foregut. The excess then moves on to the hindgut and ferments in the cecum. The presence of this fermenting carbohydrate in the cecum causes proliferation of lactic acid bacteria and an increase in acidity. This process kills beneficial bacteria, which ferment fiber. The endotoxins and exotoxins may then be absorbed into the bloodstream, due to increased gut permeability, caused by irritation of the gut lining by increased acidity. The endotoxaemia results in impaired circulation, particularly in the feet. This results in laminitis.

Insulin resistance

Laminitis can also be caused by insulin resistance in the horse (See also Equine Metabolic Syndrome, below. Insulin resistant horses tend to become obese very easily and, even when starved down, may have abnormal fat deposits in the neck, shoulders, loin, above the eyes and around the tail head, even when the rest of the body appears to be in normal condition. The mechanism by which laminitis associated with insulin resistance occurs is not understood but may be triggered by sugar and starch in the diet of susceptible individuals. Ponies and breeds that evolved in relatively harsh environments, with only sparse grass, tend to be more insulin resistant, possibly as a survival mechanism. Insulin resistant animals may become laminitic from only very small amounts of grain or "high sugar" grass. Slow adaptation to pasture is not effective, as it is with laminitis caused by microbial population upsets. Insulin resistant horses with laminitis should be removed from all green grass and be fed only hay that is tested for Non Structural Carbohydrates (sugar, starch and fructan) and found to be below 11% NSC on a dry matter basis. Soaking hay underwater may remove excess carbohydrates and should be part of a first-aid treatment for any horse with laminitis associated with obesity or abnormal fat deposits. This can have the effect of depleting the hay of soluble minerals and vitamins, however, so care with dietary balance is important.

Nitrogen compound overload

Herbivores are equipped to deal with a normal level of potentially-toxic non-protein nitrogen (NPN) compounds in their forage. If, for any reason, there is rapid upward fluctuation in levels of these compounds, for instance in lush spring growth on artificially fertilized lowland pasture, the natural metabolic processes can become overloaded, resulting in liver disturbance and toxic imbalance. For this reason, many avoid using artificial nitrogen fertilizer on horse pasture. If clover is allowed to dominate the pasture, this may also allow excess nitrogen to accumulate in forage, under stressful conditions such as frost or drought. Many weeds eaten by horses are nitrate accumulators. Direct ingestion of nitrate fertilizer material can also trigger laminitis, via a similar mechanism.

Hard ground

Whenever possible, avoid working horses on hard ground. This includes concrete or gravel roads. An indoor or outdoor arena should be periodically dragged with a rake, to loosen the soil and to prevent it from hardening. Hard surfaces increase the concussion upon the horse's feet. The greater and more prolonged the concussion, the more likely it is that the horse will contract laminitis.

Lush pastures

When releasing horses back into a pasture, after being kept inside (typically during the transition from winter stabling to spring outdoor keeping), it is important to re-introduce them gradually. Feed horses before turning them out and limit the amount of time outside (45 minutes to an hour at first, gradually increasing the amount of time) and decrease the amount fed to them beforehand, as the season progresses. If a horse consumes too much lush pasture, after a diet of dry hay, the excess carbohydrate of grass can be a shock to its digestive system. If the horse is fed beforehand, it will not eat as much fresh grass when turned out and will be less likely to founder. It is also true that ponies are much more susceptible to this form of laminitis than are larger horses.

Frosted grass

Some cases of laminitis have occurred after ingestion of frosted grass. The exact mechanism for this has not been explained but sudden imbalance of the normal bowel flora can be surmised, leading to endotoxin production.

Freezing or overheating of the feet

Cases of laminitis have been observed following an equine standing in extreme conditions of cold, especially if there is a depth of snow. Laminitis has also followed prolonged heating such as may be experienced from prolonged contact with extremely hot soil or from incorrectly-applied hot-shoeing. In either case, it is possible to understand how the circulation of the feet may become adversely affected.

Cold exposure however has been shown to have a protective effect when horses are experimentally exposed to CHO overload. Feet placed in ice slurries were less likely to experience laminitis than "un-iced" feet.

Untreated infections

Infections, particularly where caused by bacteria, can cause release of endotoxins into the blood stream, which may trigger laminitis. A retained placenta in a mare (see below) is a notorious cause of laminitis and founder.

Colic

Laminitis can sometimes develop after a serious case of colic, due to the release of endotoxins into the blood stream.

Lameness

Lameness causes a horse to favor the injured leg, resulting in uneven weight distribution. This results in more stress on the healthy legs and can result in laminitis.

This may be the cause of the laminitis which caused owners to determine to put down 2006 Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro on January 29, 2007.

Cushing's disease

Cushing's disease is common in older horses and ponies and causes an increased predisposition to laminitis.

Peripheral Cushing's disease

Peripheral Cushing's disease (or more properly, Equine Metabolic Syndrome) is an area of much new research and is increasingly believed to have a major role in laminitis. It involves many factors such as cortisol metabolism and insulin resistance. It has some similarities to type II diabetes in humans (see also insulin resistance, described above). In this syndrome, peripheral adipocytes (fat cells) synthesise adipokines which are analogous to cortisol, resulting in Cushings-like symptoms.

Retained placenta

It is common practice, in horse-breeding establishments, to check by careful inspection that the entire placenta has been passed, after the birth of a foal. It is known that mares that retain the afterbirth can founder, whether through toxicity or bacterial fever or both.

Drug reactions

Anecdotally there have been reports of laminitis following the administration of drugs, especially in the case of corticosteroids. The reaction however may be an expression of idiosyncrasy in a particular patient as many horses receive high dose glucocorticoid into their joints without showing any evidence of clinical laminitis.

No evidence exists to show the mechanism by which glucocorticoids may trigger laminitis in the horse nor is there any research definitely proving a causal link between the two.

Exposure to agrichemicals

Even horses not considered to be susceptible to laminitis can become laminitic when exposed to certain agrichemicals. The most commonly-experienced examples are herbicide and synthesized nitrate fertilizer.

Symptoms of laminitis

* Increased temperature of the wall, sole and/or coronary band of the foot.

* A pounding pulse in the digital palmar artery. (The pulse is very faint or undetectable in a cold horse, readily evident after hard exercise.)

* Anxiety

* Visible trembling

* Increased vital signs and body temperature

* Sweating

* Flared Nostrils

* Walking very tenderly, as if walking on egg shells

* Repeated "easing" of affected feet

* The horse standing in a "founder stance" (the horse will attempt to decrease the load on the affected feet). If it has laminitis in the front hooves, it will bring its hindlegs underneath its body and put its forelegs out in front called "pointing"

* Tendency to lie down, whenever possible or, if extreme, to remain lying down.

The sooner the diagnosis is made the faster the treatment and the recovery process can begin. Diagnosing Laminitis is the main problem since the general problem often starts somewhere else in the horses body.

Complications of laminitis

Separation of the hoof wall

The destruction of the sensitive laminae results in the hoof wall becoming separated from the rest of the hoof. Pus may leak out at the white line or at the coronary band.

Rotation of the third phalanx

The third phalanx, also known as the coffin bone, rotates downward. Normally, the front of the third phalanx should be parallel to the hoof wall and its lower surface should be roughly parallel to the ground surface but, in laminitis, a combination of forces (e.g., the tension of the deep digital flexor tendon and the weight of the horse) allows the coffin bone to rotate. The degree of rotation may be determined by severity of the initial attack or by how soon laminitis is detected and how soon actions are taken to treat the horse.

Penetration of the third phalanx through the sole

If rotation of the third phalanx continues, its tip can eventually penetrate the sole of the foot. Penetration of the sole is not fatal; many horses have been returned to service by aggressive treatment by a veterinarian and farrier, but the treatment is time-consuming, difficult and expensive.

Treatment

There is no cure for a laminitic episode and many go undetected. However, a horse can live with laminitis for many years, and although a single episode of laminitis predisposes to further epidodes, with good management and prompt treatment, it is by no means the catastrophe sometimes supposed: most horses suffering an acute episode without pedal bone displacement make a complete functional recovery. Rest and corrective shoeing, can help improve a horse's condition. Common treatments involve pedal bone (PIII) support (either with commercially manufactured pads, or styrofoam blacks bandaged onto the feet), analgesics (usually phenylbutazone - "bute" - or suxibuzone - a related drug with fewer gastric side effects), and a vasodilator to improve laminar blood flow. Systemic acepromazine is commonly used for this purpose, as a powerful peripheral vasodilator with the fringe benefit of mild sedation which reduces the horse/pony's movements and thus reduces concussion on the hooves. Nitroglycerine may also be applied topically to increase blood flow. With modern treatment, most laminitics will be able to bear a rider or completely recover, if the laminitis was not severe or complicated (e.g. by Equine Metabolic Syndrome or Cushing's disease). Even in these cases, a clinical cure can normally be achieved. Endotoxic laminitis (e.g. after foaling) tends to be more difficult to treat. Successful treatment requires a competent farrier and veterinarian and success is not guaranteed. Alternative therapies such as herbal and homeopathic medicine may aid recovery but require expert veterinary input.

Complications from laminitis led to the euthanization of Barbaro, 2006 Kentucky Derby winner, in 2007.

The barefoot movement

Studies on hoof health by Dr. Hiltrud Strasser(Germany) and Jaime Jackson(U.S.) suggest an alternative, optimistic view on laminitis, which is supported by proponents of the barefoot horse movement. This is a holistic approach to the disease, mainly based on pulling shoes, proper hoof care and trimming, proper diet and movement. However, definitive studies as to the benefits in laminitic equines are still lacking. Cryotherapy may be one way to effectively treat laminitis in the developmental stages.